Industrial Revolution in Britain, US and Europe | UPSC – IAS

A Global Process 1700 – 1914

Industrial Revolution Once defined – Primarily in terms of new technology in Britain and Europe, now recognized also as a global phenomenon of unprecedented transformation in social organization and political/military power.

Pre – Industrial Revolution Times

One of the key indicators of human progress has always been improvement in the tools that we use and the ways in which we organize production. Today we usually associate advanced industry with the Western world, but the most advanced civilization of pre-modern times was China of the Song dynasty (960–1279).

- China earned its reputation not only for its neo-Confucian high culture – its painting, poetry, and classical education – but also for its agricultural progress with new crops and more efficient harvesting. It produced armaments on a massive scale, including gunpowder and siege machines.

- The Song imperial government issued paper money and constructed extensive river and canal networks, which commercial ships navigated profitably. Under the Song, China was technically innovative, inventing the compass, improving the technology of silk production, ceramics, and lacquer, and vastly expanding printing and book production.

- China’s advances in iron manufacture were so extensive that deforestation became a problem in parts of the north. (Until coal took its place, wood was used to smelt the iron ore.) The iron improved the strength and durability of tools, weapons, and the construction of major building projects, especially bridges. Other parts of the world lagged behind China’s innovations in trade, commerce, and industry.

Beginning in the eighteenth century, however, Western Europe, and especially Britain, caught up with and surpassed China, and the rest of the world, in economic power and productivity. To increased concern with commerce, trade, and exploration; increased family demand for products for the household and the dining table; new technology; and commitment to financial success and the pursuit of profit. – Slowly these new economic interests led to the creation of new tools:-

- Better ships;

- New and improved commercial instruments and organizations,

- Such as the joint stock company; and

Even the adoption and adaptation of some of China’s earlier inventions, including the compass, gunpowder, and movable type for printing. Business-people in Western Europe pursued new economic possibilities with a vigor and flexibility that were sometimes admirable, as in the search for new technologies, and sometimes morally reprehensible, as in the use of millions of slaves in the creation of vast sugar plantations in the Caribbean basin and in the extraction of gold and silver from New World mines through coerced labor for the benefit of European businessmen.

All these economic initiatives – innovation at home and exploitation overseas – paved the way for the Industrial Revolution, which began in the eighteenth century.

This modern Industrial Revolution began with simple new machinery and minor changes in the organization of the workplace, but these were only the first steps. Ultimately, the Industrial Revolution multiplied the profits of the business classes and increased their power in government and public life. It broadened and deepened in its scope until it affected

- Humanity globally,

- Transforming the locations of our workplaces and homes,

- The size and composition of our families and

- The quality and quantity of the time we spend with them,

- The educational systems we create,

- The wars we fight, and

- The relationships among nations.

As a global process the Industrial Revolution – restructured the procurement of raw materials in the fields and mines of the world, the location of manufacture, and the range of international marketplaces in which new products might be sold. As the masters of the new industrial productivity adopted this global view of their own economic activities, their ventures became imperial in scope. They marshalled the powers of their governments to support their global economic capacities. Reciprocally, the governments relied on the power of industrialists and business-people to increase their own international strength politically, diplomatically, and militarily. The balance of wealth and power in the world shifted, for the first time, toward Europe, and especially toward Britain, the first home of the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution in Britain, 1700–1860 | UPSC – IAS

What events gave birth to the Industrial Revolution? | UPSC – IAS

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain around 1700, and although it is called a “revolution,” it took more than 150 years to be fully realized. During this period Britain –

- Created and mechanized a cotton textile industry, which soon became the world’s most productive;

- Created a railway network, which transformed the island’s transportation and communication systems; and

- launched a new fleet of steam-powered ships, which enabled Britain to project its new productivity and power around the globe.

Economic historians agree, however, that the industrial changes were possible because agriculture in Britain- the basis of its pre-industrial economy – was already undergoing a process of continuing improvement. The transformation was so fundamental that it is called an agricultural revolution. (This agricultural revolution in the use of new tools and implements in producing new crops for market profit was actually a second agricultural revolution. First occurred about 15,000 years ago, when nomadic peoples began to domesticate crops and animals and settle into villages.)

A Revolution in Agriculture (Industrial Revolution) | UPSC – IAS

Britain (along with the Dutch Republic, as the Netherlands was known until 1648) had the most productive and efficient commercial agriculture in Europe. Inventors created new farm equipment and farmers were quick to adopt it. Jethro Tull (1674–1741), as an outstanding example,

- Invented the seed drill (which replaced the old method of scattering seeds by hand on the surface of the soil with a new method of planting systematically in regular rows at fixed depths);

- A horse-drawn hoe; and an iron plow that could be set at an angle that would pull up grasses and roots and leave them to fertilize the land.

- New crops, such as turnips and potatoes from the New World, were introduced.

- Farmers and large landlords initiated huge irrigation and drainage projects, increasing the productivity of land already under cultivation and opening up new land.

- The word “agronomy,” the systematic concern with field crop production and soil management, entered the English language in 1814.

Governments revised dramatically the laws regarding land ownership in order to stimulate productivity. In Britain and the Netherlands, peasants began to pay landowners commercial rents that fluctuated with market conditions, rather than paying fixed, customary rents and performing compulsory labor services.

Moreover, lands that had been held in common by the village community and used for grazing sheep and cattle by shepherds and livestock owners who had no lands of their own were now parceled out for private ownership through a series of enclosure acts.

- Enclosures had begun in England in a limited way in the late 1400s. In the eighteenth century the process resumed and the pace increased. In the period 1714–1801, about 25 percent of the land in Britain was converted from community property to private property through enclosures.

- The results were favorable to landowners, and urban businessmen began to buy land as agricultural investment property.

- Agricultural productivity shot up; landowners prospered. But hundreds of thousands of farmers with small plots and cottagers who had subsisted through the use of the common lands for grazing their animals were now turned into tenant farmers and wage laborers. The results were revolutionary and profoundly disturbing to society. Peasant riots broke out as early as the middle of the sixteenth century. In one uprising, 3,500 people were killed.

The Industrial Revolution process continued throughout the period of the early Industrial Revolution as many of the dispossessed farmers turned to rural or domestic industry to supplement their meager incomes. Later, rural workers left the land altogether for new industrial jobs in Britain’s growing cities.

The capitalist market system transformed British agriculture and emptied the countryside, providing capital and workers for the Industrial Revolution. The economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) called capitalism a process of “creative destruction.” In the agricultural revolution and the Industrial Revolution we see evidence of both: the often painful destruction of older ways of life and the creation of new, uncharted ways.

A Revolution in Textile manufacture (Industrial Revolution) | UPSC – IAS

The first important commercial product of the Industrial Revolution in England was cotton textiles. Until the mid-eighteenth century, the staple British textile had been woolens, woven from the wool of locally raised sheep.

- By then, however, European traders in India realized that the cotton cloth of India was far more comfortable and far easier to clean. As they began to import these light, colorful, durable cotton textiles, the Indian fabrics began to displace woolens in the British market.

- The British government responded by manipulating tariffs and import regulations to restrict Indian cotton textiles, while British inventors began to produce new machinery that enabled Britain to surpass Indian production in both quantity and quality.

- The raw cotton would still have to be imported from subtropical India (and later from the southern United States and Egypt), but the British could create at home their own manufacturing processes that turned it into cloth, increasing British jobs and profits, and cutting back on the purchase of finished cloth in India, thus undercutting jobs and profits there.

Merchants organized much of the early industrial production through the putting-out system. They would drop off raw cotton at workers’ homes where women would spin it into yarn, which men would then weave into cloth, which merchants would later pick up.

Industrial Revolution – New Inventions | UPSC – IAS

(Spinning Jenny / flying Shuttle)

The spinning wheel, which had been in existence for centuries, allowed women to produce fairly uniform yarn. Men wove the yarn on looms that required two men sitting across from each other, passing the shuttle of the loom from left to right and back again.

- In 1733, John Kay invented the “flying shuttle,” which allowed a single weaver to send the shuttle forth and back across the loom automatically, without the need for a second operator to push it.

- The spinners could not keep up with the increased demand of the weavers until, in 1764, James Hargreaves introduced the “spinning jenny,” a machine that allowed the operator to spin several threads at once. The earliest jennies could run eight spindles at once; by 1770, it was 16; and by the end of the century, 120. Machines to card and comb the cotton to prepare it for spinning were also developed.

Thus far, the machinery was new, but the power source was still human labor, and production was still concentrated in rural homes and small workshops. Then a series of inventions led to the mechanization of the cotton industry. In 1769, Richard Arkwright patented the “water frame,” a machine that could spin several cotton strands simultaneously. Powered by water, it could run continuously.

In 1779, Samuel Crompton developed a “spinning mule,” a hybrid that joined the principles of the spinning jenny and the water frame to produce a better quality and higher quantity of cotton thread. Unfortunately, Crompton was too poor to patent it, but he sold designs for it to others. Now British cloth could rival that of India. Fascinated by Arkwright’s water frame, Edmund Cartwright believed he could make a fortune by applying the principles of the technology to weaving. After some experiments, he patented the power loom in 1785, with water power harnessed to drive the shuttle.

Meanwhile, in the coalfields of Britain, mine owners were seeking more efficient means of pumping water out of mine shafts. The key development was the steam engine. By 1712, Thomas Newcomen had mastered the use of steam power to drive the water pumps.

- In 1763, James Watt a technician at the University of Glasgow, was experimenting with improvements to Newcomen’s steam engine, when Matthew Boulton a small manufacturer, provided him with the capital necessary to develop larger and more costly steam engines. By 1785 the firm of Boulton and Watt was manufacturing new steam engines for use in Britain and for export.

- In the 1780s, Arkwright used a new Boulton and Watt steam engine instead of water power. From this point, equipment grew more sophisticated and more expensive. Spinning and weaving moved from the producer’s home or small workshop by a stream of water to new steam-powered cotton textile mills, which increased continuously in size and productivity. Power looms, such as Cartwright’s, invented to cope with increased spinning capacity, became commercially profitable by about 1800. Increasingly, in the 1800s, power looms became one of the most important technologies of the Industrial Revolution.

- The new productivity of the machines transformed Britain’s economy. It took hand spinners in India 50,000 hours to produce 100 pounds of cotton yarn. Crompton’s mule could do the same task in 2,000 hours. Arkwright’s steam-powered frame, available by 1795, took 300 hours; and automatic mules, available by 1825, took just 135 hours. Moreover, the quality of the finished product steadily increased in terms of strength, durability, and texture. Cotton textiles became the most important product of British industry by 1820, making up almost half of Britain’s exports. Prior to this mechanization, most families had spun and woven their own clothing by hand;

Thus the availability of machine-made yarn and cloth affected millions of spinners and weavers throughout Great Britain. (Industrial Revolution affect) As late as 1815 owners of new weaving mills continued the putting-out system. When cutbacks in production were necessary, the home workers could be cut. Thus the burden of recession could be shifted onto the shoulders of the home producer, leaving the mill owners relatively unscathed.

In 1791, home-based workers in the north of England burned down one of the new power-loom factories in Manchester. Machine-wrecking riots followed for several decades, culminating in the Luddite riots of 1810–20. Named for their mythical leader, Ned Ludd, the rioters wanted the new machines banned. Soldiers were called in to suppress the riots.

The textile revolution had an impact on economies around the world, devastating some, energizing others. India’s industrial position was reversed. Its markets for hand-manufactured textile were undercut by Britain’s new industrial production, and India, ironically, became the textbook example of a colonial economy, supplying raw cotton to Britain and importing machine-manufactured cotton textiles from Britain.

Industrial Revolution in United States of America | UPSC – IAS

Industrial Revolution in the United States, on the other hand, prospered, but its prosperity gave a new impetus to slavery. Britain’s new machine-operated mills required unprecedented quantities of good-quality cotton. Raw cotton was oily and full of seeds, and it was impossible to process it into yarn without first cleaning it or removing the seeds.

- In the United States, the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793 enabled workers to clean 50 pounds of cotton in the time it had previously taken to clean 1 pound. This solved part of the supply problem.

- The plantation economy of the United States revived and expanded, providing the necessary raw cotton, but, unfortunately, it also gave slavery a new lease on life.

- American cotton production rose from 3,000 bales in 1790 to 178,000 bales in 1810, to 732,000 bales in 1830, and 4,500,000 bales in 1860. Almost all the cotton was produced by slave labor. The industrialization that had begun in Britain was reshaping the world economy.

The Industrial Revolution | UPSC – IAS

The Iron Industry

Industrial Revolution – Developments in the textile industry began with a consumer product that everyone used and that already employed a substantial handicraft labor force; they mechanized and reorganized the process of production and relocated it from homes and small workshops to large factories. Other industrial innovations created new products.

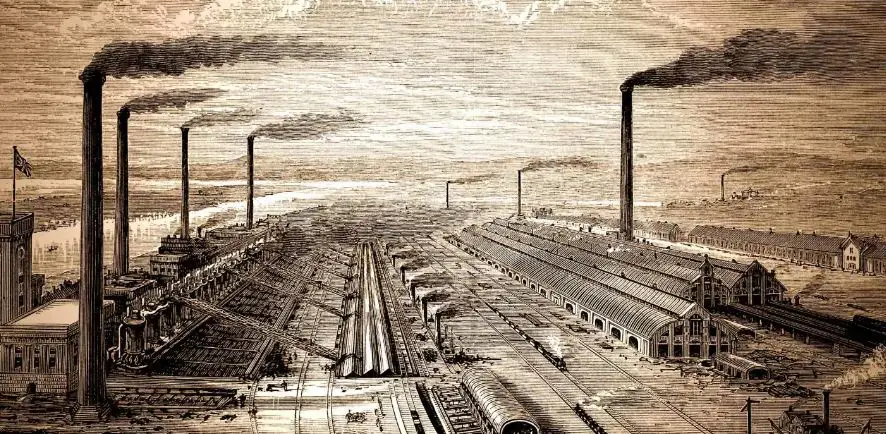

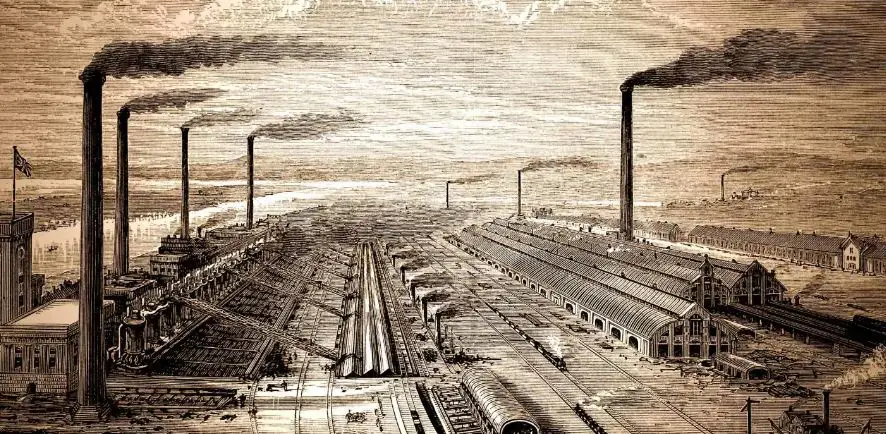

Britain’s iron industry, which had been established since the mid-1500s, at first burned wood to heat iron ore and extract molten iron, but by about 1750 new mining processes provided coal, a more efficient fuel, more abundantly and more cheaply. About 1775, the iron industry relocated to the coal and iron fields of the English Midlands. A process of stirring the molten iron ore at high temperatures was introduced by Henry Cort in the 1780s. This “puddling” process encouraged the use of larger ovens and integrated the processes of melting, hammering, and rolling the iron into high-quality bars.

in Industrial Revolution times productivity increased dramatically. As the price of production dropped and the quality increased, iron was introduced into building construction. The greatest demand for the metal came, however, with new inventions:-

- The steam engine,

- Railroad track and locomotives,

- Steamships, and new urban systems of gas supply

- And solid and liquid waste disposal all depended on iron for their construction.

Britain’s world market share of iron multiplied from 19 percent in 1800 to 52 percent in 1840—that is, Britain produced as much manufactured iron as the rest of the world put together. With the new steam engine and the increased availability and quality of iron, the railroad industry was born. The first reliable locomotive, George Stephenson’s Rocket, was produced in 1829. It serviced the Manchester–Liverpool route, reaching a speed of 16 miles per hour.

- By the 1840s, a railroad boom swept through Britain and Europe, and crossed the Atlantic to the United States, where it facilitated the westward expansion of that rapidly expanding country.

- By the 1850s, most of the 23,500 miles of today’s railway network in Britain were already in place, and entrepreneurs found new foreign markets for their locomotives and tracks in India and Latin America.

- The new locomotives quickly superseded the canal systems of Britain and the United States, which had been built mostly since the 1750s, as the favored means of transporting raw materials and bulk goods between industrial cities.

- Until the coming of the steam-powered train, canals had been considered the transportation means of the future. (The speed with which the newer technology displaced the older is one reason historians resist predicting the future. Events do not necessarily proceed in a straight-line process of development, and new, unanticipated developments frequently displace older patterns quite unexpectedly.)

- Steamships, using much the same technology as steam locomotives, were introduced at about the same time. The first transatlantic steamship lines began operating in 1838. World steamship tonnage multiplied more than 100 times, from 32,000 tons in 1831 to 3,300,000 tons in 1876. With its new textile mills, iron factories, and steam-driven transportation networks, Britain soon became the “workshop of the world.”